When you arrive in Tbilisi border agents do not just stamp your passport, they also give you a wine bottle. Georgia is a country of mountains sandwiched in between Europe and Asia. The border agents don’t just stamp your passport, they also give you a bottle of wine.

At the Georgian dinner table, it’s easy to forget about time. A recent trip to Georgia’s capital saw me join friends for an evening of a dizzying variety of salads. This was followed by gallons and gallons orange wine and a few forays in polyphonic harmonies – a trademark feature of Georgian folkmusic. As I staggered back to my 4 am hotel, I was delirious and felt as if I had just woken up from a culinary nightmare.

You don’t have to fly to the Caucasus in order to enjoy a supra. Five Georgian restaurants opened in New York City only in the past three years. Georgia’s orange wine is becoming more popular across the nation. It was once only known by the most savvy sommeliers. Some are calling it the “new rose”. The Georgian Feast by Darra Goldstein, a cookbook that is unmatched in its encyclopedic nature, has just been released in a second edition.

The Georgian Palate

Why are foodies drawn to this tiny sliver of land smaller than South Carolina, so far away? It’s difficult to find a dish that combines Eastern and Western cooking techniques so well. For example, the soup dumplings called khinkali are just as popular in Tbilisi and Shanghai. Georgia’s flatbreads are similar to India’s finest naan and are puffed up and scorched inside traditional clay tone ovens.

The similarities between the two are not coincidental. Georgians, who sat at the crossroads of ancient East-West routes, had the benefit of being able pick out the best from what the Greeks and Mongols as well as the Turks and Arabs cooked along the Silk Road. Alexander Pushkin, the Russian poet who said that “every Georgian meal is a poetry,” was referring not only to taste and presentation but to the fusion of cultures.

Georgian cuisine remains true to its roots despite these influences. While meat stews in Georgia may have a sweet and tart flavor, as they do elsewhere, pomegranate and sour fruits leather are likely to be the main ingredients, not prunes or apricots. Georgian tomato, a staple of summer, is similar to Mediterranean versions, but it has a different flavor, with toasty notes coming from sunflower or walnut oils.

Walnuts are a staple in Georgian cuisine. In pulverized form, it is often used in soups and sauces in the same manner as the French do with butter. It can be finely chopped, candied with honey and made into a simple but satisfying dessert, gozinaki.

In Georgia, chefs are devoted to sourcing local ingredients, even if they don’t grow them themselves. This loyalty to freshness may explain why regional variations in Georgian food have survived into the 21st Century, despite Carrefour’s arrival and the arrival of other international supermarkets. Adjara Guria and Samegrelo in the west, for example, have stews that are brick-red from adjika, a chili-garlic paste. You’ll reach for your water glasses. Kakheti, in the east, is a place of milder cuisine, and the meats are lightly spiced.

There are some dishes that you should not leave Georgia or a Georgian Restaurant without trying. These are the dishes that I can’t live without. They’re the unforgettable bites which keep Georgia in my mind and my kitchen.

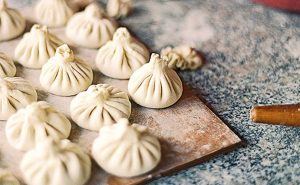

Khinkali

It is said that you can tell if a khinkali or Georgian soup dumpling is good by the number of folds: According to tradition, anything less than 20 folds is amateurish. When a plate of pepper-flecked, khinkali is placed on the table for dinner, it’s not everyone’s priority to count pleats. It’s eating the khinkali that requires both urgency and exacting techniques. If you don’t learn the latter, then you may be teased by Georgians. The first thing to know is that khinkali should be eaten with your hands. Make a claw and grab the dumpling by its topknot. Biting a small opening in the side of the dumpling, tilt your head forward to slurp the broth out before you sink your teeth into its filling. Then, discard the topknot and swig a few beers, then sigh in pleasure. Repeat.

Historians believe that khinkali, which are similar to Central Asian Manti were brought to the area by the Tartars who ruled Georgia and Armenia during most of the 13th Century. The best houses are located in Pasanauri a village about 50 miles from Tbilisi. Wild mountain herbs such as ombalo and summer savory accent the filling. Khinklis Sakhli, a local favorite in Tbilisi, is a great alternative if a khinkali journey is not in the cards.

Mtsvadi

Mtsvadi , Georgia’s common name for meat cooked on a stick over an open fire is . Georgians are purists who prefer to use salt instead of marinades or rubs. Here, beef or lamb is the preferred protein. It can be threaded on a skewer with vegetables or cut into pieces and threaded. Let me make it clear: mtsvadi is anything but bland. Especially when served with tkemali. This sour plum sauce that Georgians drizzle over everything from bread to potatoes to fried poultry.

Khachapuri Adjaruli

The amount of sulguni in khachapuri Adjaruli alone is enough to send a lactose intolerant friend to the ER. The decadence does not end there. A baker separates the cheese seconds after the bread has been removed from the ton, so that a crackled raw egg and chunks of butter can be added as a final flourish. You must use your spoon with confidence to vigorously stir the ingredients until you see hypnotizing spirals. God forbid that the mixture gets cold, but at this point you should tear off a piece of bread and dip it in.

Adjarians eat khachapuri in this way. It is a cheese-filled bread sold at bakeries all over the country. While each region has its favorite iteration of khachapuri–vegetables, meats, or legumes may be added–khachapuri Adjaruli has eclipsed the competition to become Georgia’s national dish.

Churchkhela

The lumpy, colorful confections that hang in shopfront windows are often mistaken by tourists for sausages. It takes practice and patience to make churchkhela. Concentrated grape juice, left over from the annual wine harvest, must be repeatedly poured over walnut strands. Each layer of grape juice is allowed to dry, until the walnuts are covered in a waxy, chewy coating. Churchkhela are a great source of sugar and protein. They were even used by the Georgian army as a shelf-stable food. Churchkhela is more commonly served in homes with coffee and postprandials, but they will soon be on American cheese boards.

Tklapi

When I first saw tklapi I thought it was just a placemat. This flat, colorful and more than a foot wide Georgian specialty is a Fruit Roll-Up, at its most primitive: pureed fruits, spread thinly on a sheet, and dried by the sun. The sweet tklapi, such as those made with figs or apricots, are great to eat by themselves. However the sour tklapi–packed with tart cherries and wild plums- is best used in soups and stews. Stop at the roadside shacks that sell tklapi along the highways just outside the town to find the best. You can be assured of a quality product, even if the villagers don’t speak English.

Lobio

Who knew that the kidney bean could be so versatile? Salobie in Mtskheta, which specializes in this dish, has a menu dedicated to lobio. I found my eyes widening as I ate spoonful after spoonful. Lobio is a texture somewhere between refried bean soup and a mashed-up refried bean. It is made by pounding the beans with a pestle and mortar. But the real surprise is the flavor. A slurry of fried onion, cilantro, vinegar and dried marigold is added to the pot right before serving.

Lobio’s faithful sidekick, mchadi is a griddled Cornbread with a single function. It’s one Georgian bread that does not rely on tone. Mchadi is easy to make with just three ingredients: cornmeal, water, and salt. It takes about 30 minutes from start to finish.

Kharcho

Kharcho has become so popular in the region, that Russians include it as a staple of their winter menu. Amber-colored and smelling of khmeli, suneli, and cilantro, the kharcho is made with beef or chicken, which are seasoned, seared, and then tucked in a sauce that’s rich with walnuts, and topped with torn pieces of sour, tklapi. The meat will be infused with spices and fall off the bone after a few hours.

Pkhali

Georgian cuisine is dominated by elaborate vegetarian dishes. In a land where meat has traditionally been reserved for special occasions and only served on rare occasions, this shouldn’t be surprising. Pkhali is a family salad that’s better described as a vegetable pate. It can be made from any vegetable (beets carrots and spinach are popular) and served with bread. It’s also foolproof: Simply boil your veg, puree it, then add some minced garlic and lemon juice. You can also throw in some ground walnuts and cilantro for good measure. Georgian chefs will prepare several different types of pkhali and serve them together, sprinkling pomegranate seed on top.

Lobiani

A staircase that leads underground is unmarked and bustles with people. You’ll find one of the oldest bakeries in the city, where lobiani are flaky disks filled with bean-filled dough and burnished over wood fire. They’re sold to a captive crowd day after day, every year. What is so appealing about bread and beans? Lobiani, a meal-in-a-handle that costs less than $2, is an excellent choice. This flatbread, despite its simplicity, is a delight of textures and flavors. The outer edge shatters like a croissant in Paris, revealing a center filled with spiced beans and bacon-scented butter. If I had a beer on my hand, I couldn’t think of a better food for tailgating or picnics.